NASA

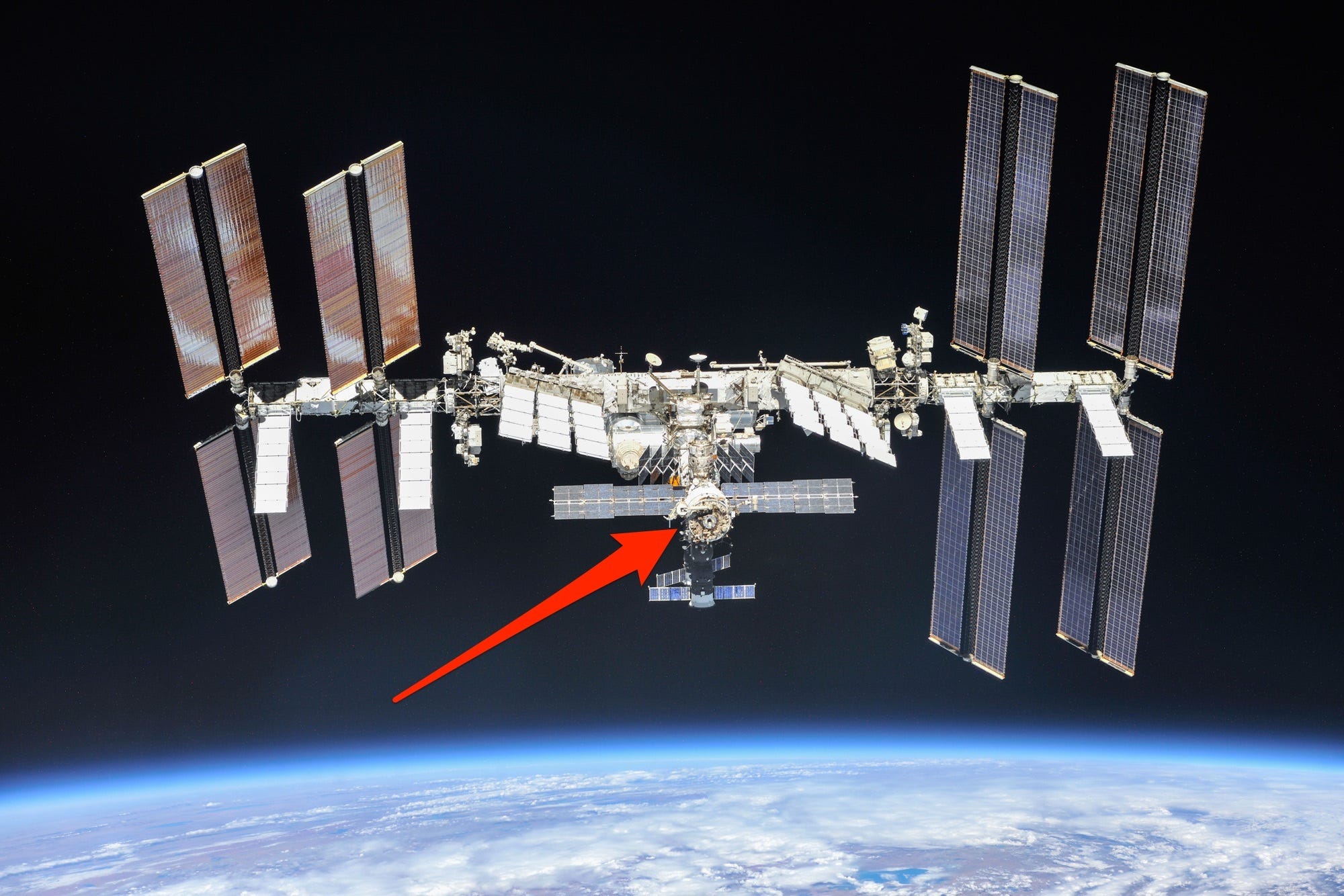

- NASA and Roscosmos determined that a leak on the International Space Station is located in the Zvezda Service Module module on the station’s Russian side.

- That module provides crucial life support, including oxygen.

- Engineers are still working to pinpoint the leak’s exact location within the module.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

On Monday night, NASA flight controllers woke the three men living on the International Space Station. A small air leak seemed to have grown quickly, and ground control wanted to find it fast.

NASA and Roscosmos, Russia’s space agency, had already narrowed down the likely location of the leak to several modules on the station’s Russian side.

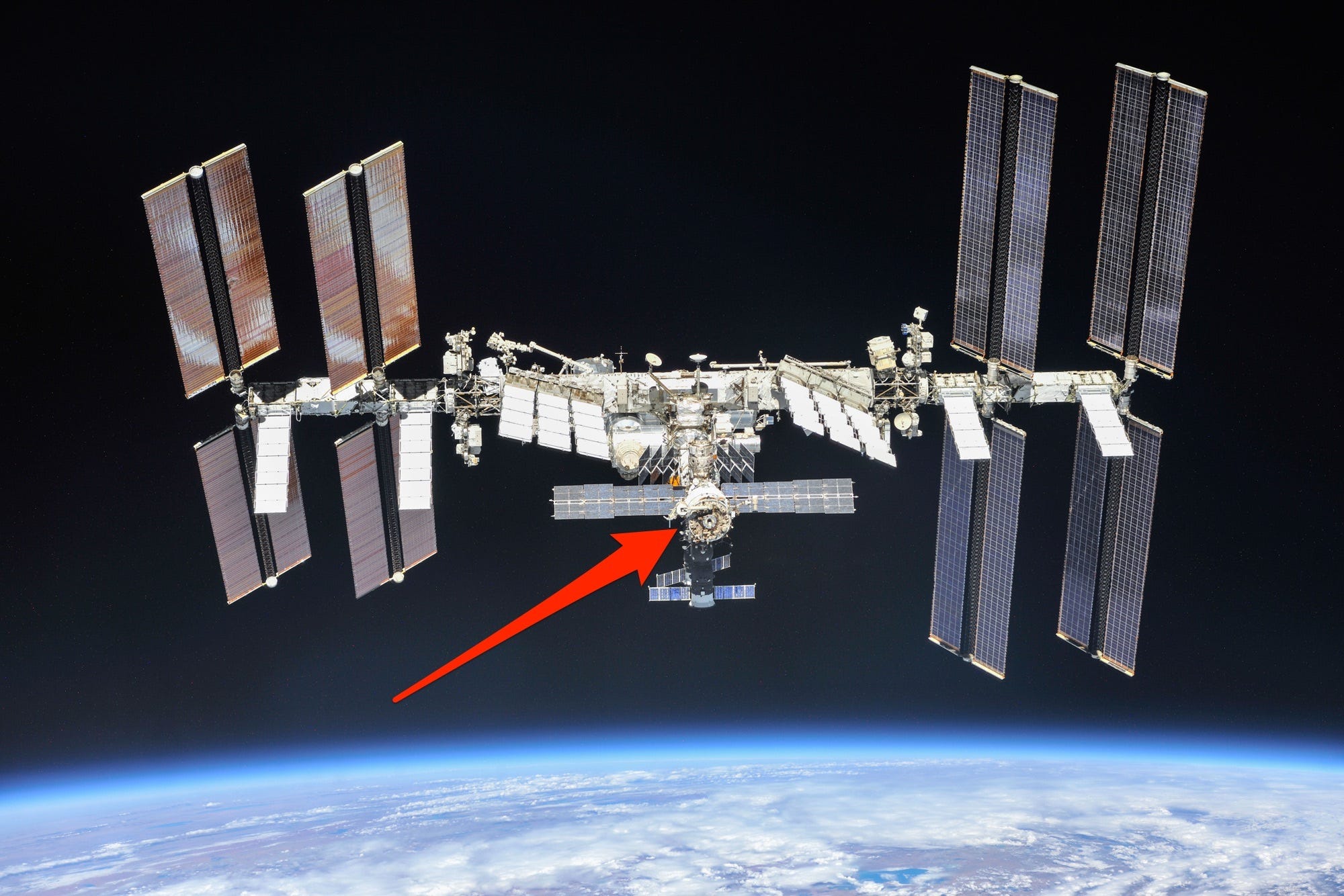

So astronaut Chris Cassidy and cosmonauts Anatoly Ivanishin and Ivan Vagner tested those modules by shutting the hatches between each one and using an ultrasonic leak detector to collect data through the night. The tool measures noise caused by airflow too quiet for humans to hear.

By Tuesday morning, they’d figured out that the leak is in the Zvezda Service Module, the main module on the station’s Russian side. Zvezda provides that half of the station with oxygen and drinkable water, and it’s also equipped with a machine that scrubs carbon dioxide from the air. The module contains the section’s sleeping quarters, dining room, refrigerator, freezer, and bathroom.

NASA

NASA and Roscosmos still haven’t pinpointed the source of the leak within the module, but they know it’s in Zvezda’s cylindrical “work compartment,” where crew members live and work.

"Additional work is underway to precisely locate the source of the leak," NASA wrote in a blog post on Tuesday morning. The agency added, however, that further investigation revealed the leak "poses no immediate danger to the crew at the current leak rate and only a slight deviation to the crew's schedule."

That's because the leak did not actually change suddenly; the shift detected this week turned out to be related to "a temporary temperature change" aboard the station, NASA wrote.

Air has been leaking from the station for more than a year

The International Space Station always leaks a little air. Normally, the air it loses gets replaced by highly pressurized containers full of a mix of oxygen and nitrogen. These are sent up on resupply missions and designed to mimic Earth's breathable air.

But in September 2019, officials noticed that the regular rate of air loss had increased. The change wasn't major, but then this summer, they saw a new uptick in that already higher-than-usual rate.

So in August, crew members aboard the station began testing for leaks by sealing each section off and monitoring air pressure. They sealed themselves in the Zvezda module for the duration of the initial, four-day test, so didn't assess it.

Because those tests didn't find any leaks, NASA concluded that the source must have been in one of the two models not assessed: either the Zvezda module or the Poisk Mini-Research Module 2, which serves as a port for docking spaceships and a place where crew members prepare for spacewalk.

NASA

"With the crew living and working in these modules, it was impossible to achieve the proper environmental conditions necessary for this test," a NASA spokesman, Daniel Huot, previously told Business Insider.

NASA and Roscosmos were hesitant to seal off and test the Zvezda module, however, because it connects directly to the Soyuz spacecraft attached to the ISS. Ivanishin, Cassidy, and Vagner would need to use that ship get back to Earth in an emergency, so closing the module's hatches decreases the crew's ability to make a quick getaway.

However, by Monday night, controllers on the ground decided that sealing off Zvezda was worth the risk.

"At that point, we made the decision that it had gotten large enough, that we felt like we had a pretty good opportunity to to get the crew up, start working through a more focused isolation procedure," Kenny Todd, deputy program manager for the space station, told reporters on Tuesday.

The test went smoothly. While Zvezda was inaccessible, the crew relied on the life-support system on the US side of the station, which also has oxygen generators, a kitchen, and drinkable-water systems.

A busy time for the space station

The crew members located the leak ahead of a busy time for the ISS. This weekend, a Northrop Grumman spacecraft is slated to bring up an experimental new toilet and other supplies. Then on October 14, the next crew members are expected to launch to the station from Kazakhstan: NASA astronaut Kate Rubins and cosmonauts Sergey Ryzhikov and Sergey Kud-Sverchkov.

SpaceX via NASA

At the end of October they'll be joined by the members of NASA's Crew-1 mission, the next in the agency's partnership with SpaceX: NASA astronauts Shannon Walker, Victor Glover, and Michael Hopkins, and Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency astronaut Soichi Noguchi.

NASA was originally aiming to launch Crew-1 this month, but the timeline has been pushed back to October 31. That's mostly to accommodate other mission schedules, though also in part because of the leak.

The delay, NASA wrote in a blog on Monday, "will provide a good window of opportunity to conduct additional testing to isolate the station atmosphere leak if required."

Cassidy, Ivanishin, and Vagner are expected to return to Earth shortly before the Crew-1 group arrives.

Not the first leak on the space station

NASA via Chris Bergin/Twitter

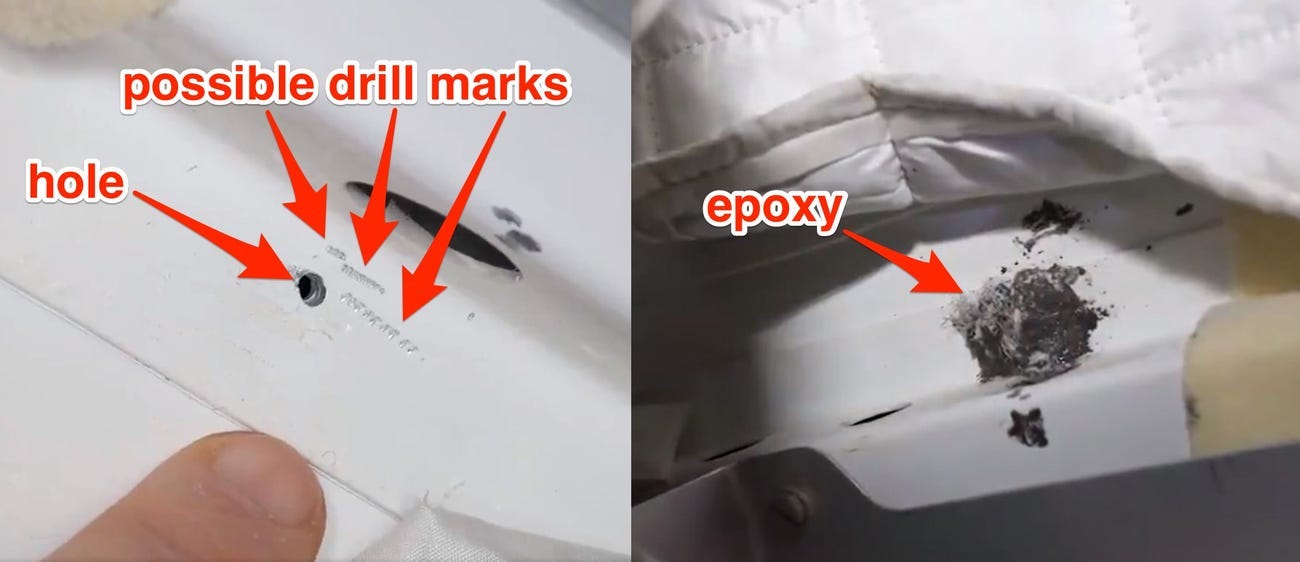

This isn't the first leak found on the space station's Russian side. In August 2018, crew members discovered a 2-millimeter drill hole in part of a Russian Soyuz spaceship that was docked to the station.

That hole seemed to indicate a manufacturing defect — it appeared that someone on Earth had attempted to plug it with paint, but that paint had broken off. So in December 2018, two cosmonauts donned spacesuits and studied the hole in detail on a spacewalk. They spent nearly eight hours hacking at the insulation with a knife to find and document it.

After that, the crew patched up the hole with an epoxy sealant. Roscosmos has since stayed quiet about the incident.

"We know exactly what happened, but we will not tell you anything," Roscosmos head Dmitry Rogozin said at a youth science conference in September 2019, according to the Russian state news agency Ria Novosti.